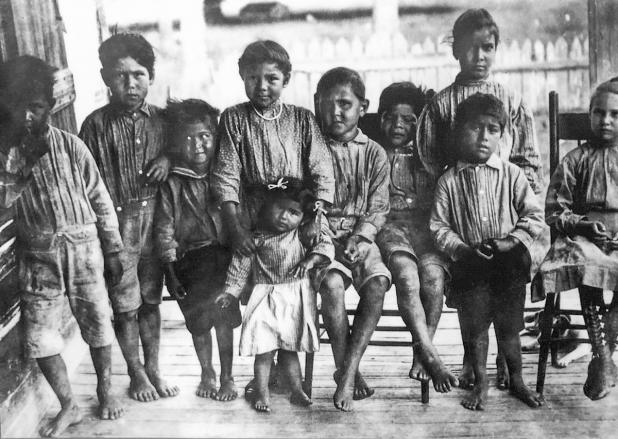

Indian children, some of whom were orphaned after the murders of their parents.

The balls and bullets the author discovered on his property.

The Killings of Jules Darden and Oliver Paul

(Editor’s Note: This is not a news story; nor is it a feature story. It is a recollection of a time the author did not live, but the events of that time have been handed down via oral tradition and outside documentation of the Chitimacha People. It is a snapshot of an era long forgotten by most, held close to the heart by a few.)

Dr. Mark Raymond Harrington was born in 1882.

He was an anthropologist and archaeologist most renowned as the curator of archaeology for the Southwest Museum from 1928-1964, and is regarded as a pioneer in Native American studies. He died in 1971.

Known as “M.R.” by his closest friends and associates, Harrington’s thousands of papers include a brief discussion on the Chitimacha Tribe of Louisiana at The Society of American Indians conference the week of Oct. 2-7, 1912, at Ohio State University.

Titled “Grievances of the Chitimacha Indians Living Near Charenton, St. Mary Parish, Louisiana,” Harrington’s remarks were delivered at the behest of a formerly powerful indigenous people “very much disturbed over some recent murders of members of their tribe by white men who were never brought to justice.”

***

Oddly enough, it took a hobby of mine 23 years ago to resurrect the memory of my grandmother, Faye Rogers Stouff, wife of Emile Anatole Stouff, at her kitchen table, drinking coffee and telling me about our people.

In 1840, a young Indian man set out to build a home on Bayou Teche just outside of Charenton.

His name was Alexander Darden, and he was my ancestral uncle. He built, with the help of other tribal members, a three-room house that was, at times, home to two or three families.

This was 122 years after the war between my ancestors and the French that lasted from 1706 to 1718. After the truce was made, the Chitimacha—who once were the most powerful tribe in the state, occupying nearly a third of its lower reaches—virtually vanished from any historical record until the late 1800s.

I live in that home today, though much altered over the nearly 180 years hence; it has been added to, renovated, restored, raised, roofed and fussed over. A portrait of Alexander hangs on the wall inside.

In 1883, Albert S. Gatschet visited the tribe on behalf of the U.S. Bureau of American Ethnology, and those long-secluded indigenous people emerged from a cultural blackout of more than a century.

***

Harrington said in 1912, “The murderers were not even arrested; consequently the Indians go about their work in fear of their lives.”

The professor was not one to mince words. The Indians wished to move away from such a darkness that had come upon them to “raise their children without the feeling that they were bringing them up only for some drunken white men to kill.” The Chitimacha asked Harrington to “lay the facts before some officer of the government” to prompt an investigation.

“I took evidence in (two cases) from Benjamin Paul, the Chitimacha Chief, and from Christine Paul, his wife, (and) from Delphine Stouff, a Chitimacha woman, and Octave Stouff, her white husband.”

Of the two cases Harrington was asked to relay to officials, the first was on Christmas Day, 1901. He called it “the cold-blooded slaughter of and Indian woman and two Indian men, entirely innocent of wrong-doing, in their yard…by three white men.”

The second was, he said, “the murder of an Indian in a barroom at Charenton, at the hands of white men, identity not known” on Feb. 23, 1908.

***

Sometimes, when I make my drive to work, or divert on my way home to pick up a few groceries at Raintree Market, I am reminded that beyond the well-lit course of Ralph Darden Memorial Parkway and the tall red spire of the casino that has brought prosperity to a people who just over a century ago hid away in the swamps to survive annihilation, I think of those long ago crimes.

Christmas Eve, 1901. I recall Christmas Eves through the eyes of a child, gazing at the presents under the tree, the smell of mom’s exquisite dinner, my grandparents with us at the table. But Oliver Paul and Jules Darden, on the day before Christ’s birth, could not have known what lay ahead.

This is history, scrutinized with full consideration of the people who relayed it to Harrington. It is today shrouded in the mists of time. Stories, as are their nature, are seen through the eyes of witnesses, or from the mouths of others. It is human nature that we take the sides of those like us, and eschew the perception of the other. There are names in these stories that, out of respect, shall not be written, except for those who were acting in an official capacity of that day and place. Of the dead, their honor is in their naming.

***

Harrington continued in his speech to the conference, “Gabriel Mora, an Indian, had been drinking a little and got into a fight with a Negro at Charenton, no harm resulting to either combatant. Jules Darden, another Indian, took Mora home and went back (to Charenton) to buy something for Christmas.

“When he was in Charenton he was accosted by Alfred Pecot, a deputy sheriff, who demanded to know what he had been doing. Darden replied that he had not been doing anything…as he had not been mixed up in the fight. The deputy tried to strike him, but the Indian held the officer off. While they were scuffling, the crowd attacked the Indian, threw him down and beat him severely. Darden would have been killed if it had not been for his sister, Delphine Stouff, who dragged him unconscious away from the crowd.

“The deputy wanted to shoot her, but someone in the crowd persuaded him to refrain.”

It was Christmas morning that the deputy, Alfred Pecot, accompanied by two other men, returned to the house of the Paul family. They called out Oliver Paul, an Indian, who had nothing to do with the fight, Harrington said.

Three of the Paul men went to the gate to meet the arrivals, unarmed, while the others had guns. “They found that the white(s) wanted to arrest the boy Oliver, but would not tell what he was charged with and had no warrant to show.”

Oliver came from the house and denied that he had done anything wrong. The deputy drew his handcuffs and ordered the boy to come to him. Frightened by the guns and handcuffs, Oliver fled.

“The boy turned and started to run back to the house, when he was fired upon by all three whites and instantly killed,” Harrington relayed. “Three Winchester balls penetrated his body.”

His father cried, “You have killed my boy!” and the white men knocked him down with their guns and began to beat him, when the old man’s daughter, Jules Darden’s wife, ran out and tried to stop them. They shot her in the head and she died shortly thereafter.”

What followed could have been much worse, but Harrington reports that “when Jules heard his wife’s scream he fired at the white (man) from the window with a shotgun. The whites left in a hurry and gathered a mob in Charenton to come back and massacre all the Indians.” However, local priests intervened and stopped the bulk of the violence.

The sheriff came the next day and arrested the Indian men involved, held them in jail on charges of resisting an officer, and they were later released. The murderers, Harrington said, were never arrested.

Of Jules, his miseries were not over. On Feb. 22, 1908, he went to the barroom. Harrington wrote that he “never went armed, and had always borne a good reputation. At 11 o’clock that night, two colored boys, one 12 years old, the other 14, brought back his body in a wagon, fairly cut to pieces, thirteen cuts on his body and his skull crushed. Although he was still alive when brought in, he died shortly after.”

The case did go before the St. Mary Parish Grand Jury, which returned a “no true bill.”

***

Regrettably, there are no known photos of Jules Darden or Oliver Paul.

The Paul home still stands, just down the road from mine, constructed within the same approximate time period and style of the era. I pass it every day, to and from work, or elsewhere. There is little to no word of what other members of the tribe did, or did not do, what they felt or how they reacted, other than Harrington’s description of their plea to move elsewhere, which was obviously never accomplished.

The tribe’s fortunes were never rosy, but they did improve with the assistance of an unexpected source: Tabasco.

Sisters Sarah McIlhenny and Mary Bradford learned about the majestic baskets crafted just a couple dozen miles from the salt dome on Avery Island near New Iberia, and embarked on a mission to not only empower Chitimacha women, but also provide revenue.

Those baskets were sold by art dealers and shops in cities far and wide. Moreso, when the sheriff ordered tax sales of the Indians’ scant acreage of land, which they were still unable to pay, the sisters stepped in and paid the taxes, and further, used their clout to have Congress put the property into federal trust protection.

My grandmother told me this story when I was far too young to understand the ramifications, the meaning of it. It stuck with me for a long, long time, but the passing of years tucked it away somewhere in the far reaches of my memory, seldom touched.

Then there was that hobby I mentioned.

I’ve many hobbies, one of which is metal detecting. It was something I picked up back in the mid-1990s and eventually gave up in the early 2000s until just a few months ago. I have been searching my property, found a few decent coins, mostly iron and junk.

But in my front yard, the first time I was detecting, I unearthed the history of what has been related here.

Within a space perhaps 20x20 feet square I dug 10 bullets, ranging from round “musket” type to rifle and pistol rounds, all concentrated in that area. I had completely forgotten about my discovery all these years later. But last week, I unearthed another small caliber lead slug in the same area.

It all came back to me then. My grandmother, weaving a traditional Chitimacha basket, the steaming coffee cup on the table, the stories she told me…including the deaths of Jules Darden and Oliver Paul.

Certainly, the evidence is circumstantial. Yet, the events my grandmother related largely coincide with what Harrington was told so long ago. In her telling and in my mind’s eye, there was a gunfight, and there were Indian men beyond the gate between the house and the old dirt road, perhaps sheltered behind a tree or some long-ago outbuilding, and 11 bullets bear witness to a time when there were no laws to protect the people living on that bend of Bayou Teche. The bang of percussion caps, perhaps old muzzleloaders, small caliber arms, still resound in the crisp, cool air of Christmas, 1901 and February, 1908.

These are but two stories, there are most certainly more. They float, sometimes, into our presence, because the Indian lived in circular time, wherein the past will now-and-then return to the present, and all things circle back to where they began.

And in their telling, there is a message that I hope we descendants of those who died will also bear close to the heart:

“We are still here.”