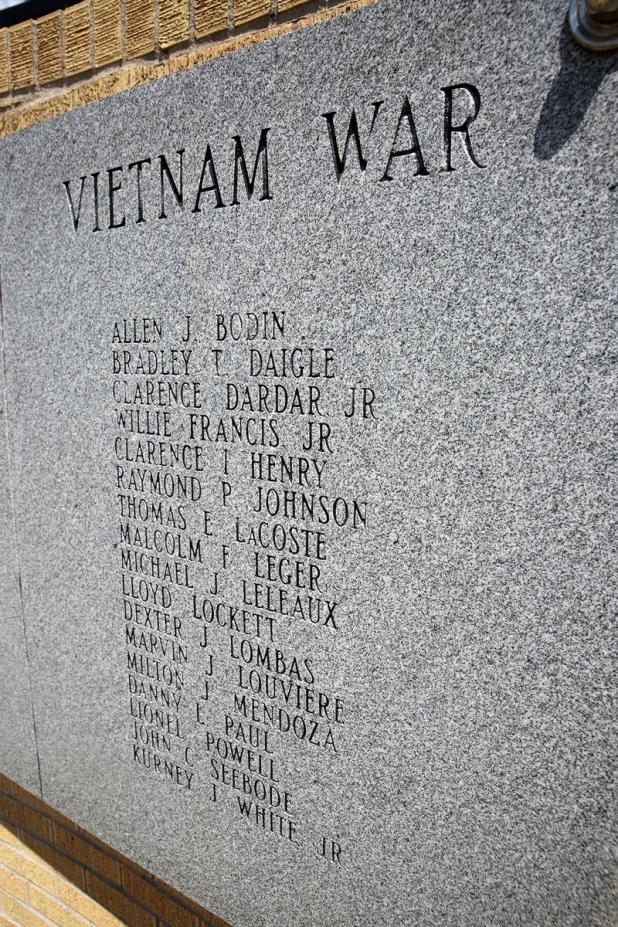

The St. Mary Parish War Memorial on U.S. 90, below, includes a stone panel on which are inscribed the names of 17 parish men who died in the Vietnam War.

From the editor: PBS documentary raises the old questions

Sammy Roberson was a smallish guy, or so I remember him. I never saw Sammy when he wasn’t behind the wheel of his car.

A picture, probably from high school in the mid- to late 1960s, shows Sammy in a suit and tie. His carefully combed hair was a little out of control. He had a friendly, slightly gap-toothed grin.

After he left school, he worked with my dad at a rural Missouri factory.

Dad worked there during the day and raised hogs when he got home. Dad overslept a lot.

When he did, and Sammy pulled up in front of our house to pick up Dad for work, it was my job to run out and ask Sammy to hang on for a few more minutes. I was maybe 11.

One day, I overheard Mom and Dad talking about Sammy. He’d been drafted.

In those days, getting drafted meant going to Vietnam. And from the way the folks talked, Vietnam wasn’t at the top of the list of places Sammy wanted to go.

Sammy went.

And on April 4, 1970, in Quang Tri Province in South Vietnam, Army Pfc. Samuel L. Roberson, 20, of Bland, Missouri, was killed as a result of enemy action. He was one of two men from our little county of 12,000 who died in Southeast Asia.

In 40 years of reporting, I've been privileged to interview veterans going all the way back to World War I. But Sammy Roberson was the only casualty of war who touched my life in that way.

The St. Mary veterans memorial on U.S. 90 has a panel in which the names of 17 parish men who died in Vietnam are inscribed. So I know the war touched lives here, too.

Sammy came to mind again this week as I’ve watched the “The Vietnam War,” the Ken Burns and Lynn Novick documentary on PBS. It concludes this week.

It’s natural to think of loss when we think of that war. Sometimes it seems that the only thing we got from that war was loss.

The documentary raises a lot of the old questions: Was fighting communism enough justification, even when the government we fought to defend was corrupt and incompetent?

Didn’t the domino theory prove to be true? Didn’t the communists take over in Cambodia and Laos after Vietnam fell? Didn’t communists kill hundreds of thousands of Cambodians?

Were the Americans who fled to Canada to get out of the draft cowards? Or were they, as one wheelchair-bound vet said in a class discussion at college, the real heroes?

Where’s the line between protest and treason?

Should our government lie to us if the end cause is noble? Which causes are noble? Who decides?

Have we finally decided to stop blaming brave young people for the messes that frightened old people put them in?

We’ve surely had opportunities to ask those questions again since Saigon fell on that terrible night in April 1975, when people clung to the skids of Huey helicopters lifting off from the roof of the U.S. embassy.

If there’s any consolation to be had in remembering Vietnam, it’s the way the courage of young Americans can redeem our doubts and missteps. Two notable examples involve men from South Louisiana.

One of them was Hugh Thompson, a Georgia native who flew helicopters for the energy industry after the war and then served as a Louisiana Department of Veterans Affairs counselor for Acadiana.

During the war, Thompson and two crewmen put their helicopter and its guns between rampaging American soldiers and villagers of Son My during what became known as the My Lai Massacre. At least 354 Vietnamese civilians, and maybe as many as 500, were killed based on

faulty intelligence that said the mostly peaceful rice farmers were in cahoots with the Viet Cong.

Two officers, Capt. Ernest Medina and Lt. William Calley, were brought before courts martial in connection with My Lai. To many, including officials in the Nixon administration, Medina and Calley were heroes being unjustly accused. Smearing Thompson looked like the way to keep them out of the stockade.

And Thompson did get attacked, even during congressional testimony. But by the late 1990s, when he went to Vietnam and met with My Lai survivors, Thompson’s heroism was recognized. Former U.S. Sen. John Breaux nominated Thompson for a Nobel Peace Prize.

Thompson died in 2006.

Stephen Bennett of Youngsville was another kind of pilot who showed another kind of bravery.

During North Vietnam’s Easter 1972 offensive, several hundred North Vietnamese regulars attacked a platoon of South Vietnamese soldiers not far from where Sammy Robertson had been killed two years earlier. That’s according to the account in Air Force magazine.

Bennett and his Marine observer, Mike Brown, were in a prop-driven two-seater, the OV-10, on their way to Da Nang after a mission when they heard the South Vietnamese soldiers’ call for help. Bennett tried to call in air support, but this was 1972 in Vietnam, and there wasn’t any. Artillery fire wasn’t practical because the enemy troops were so close to the South Vietnamese.

So Bennett and Brown flew to the rescue. They trained the OV-10’s four machine guns on the North Vietnamese. Brown, who runs a gun shop in Texas now, told me a few years ago that they were able to drive the enemy soldiers back on four passes.

But as they came around for a fifth, the OV-10 was hit, either by a surface-to-air missile or a rocket-propelled grenade. Bennett gave the order to bail out, but Brown was wounded and his parachute ripped to shreds.

So Bennett made the decision to make the 15-minute flight to the Gulf of Tonkin and ditch the OV-10 so Brown could get out safely.

One problem there: No pilot had ever survived an attempt to ditch an OV-10. Brown said Bennett knew that, and decided to ditch the plane anyway. That was the only way Brown was going to survive.

When Bennett put the plane in the water, Brown was able to get out. Bennett was killed.

Bennett’s family received his posthumous Medal of Honor on Aug. 8, 1974, from Gerald Ford on the first day of Ford’s presidency.

Brown said later that he’d made a study of Medal of Honor winners. Most, he said, made some snap decision, like those who dove on grenades to save their comrades. Others made decisions that they surely knew would result in their deaths and still kept their resolve long enough to perform their feats of courage.

Bennett belonged to the second category, Brown said.

There's one answer to one question, at least.

Bill Decker is managing editor of The Daily Review. Reach him at bdecker@daily-review.com.