This photo, taken by John K. Flores, was displayed at the 2016 event marking the removal of the black bear from the Endangered Species List.

Submitted Photo

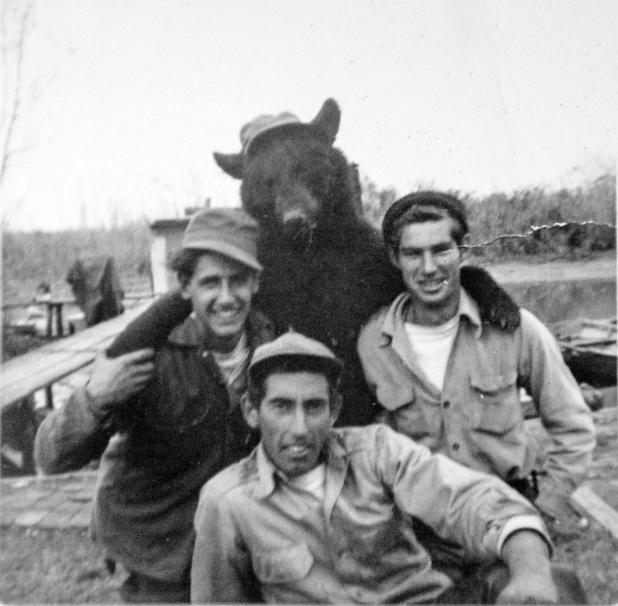

This black bear was killed by hunters in 1956. Pictured from left are James Duay, Elmer Bernadou and an unidentified hunter.

The Review/John K. Flores

This ceremony in March 2016 marked te removal of the black bear from the Endangered Species List. Former Wildlife & Fisheries Secretary Robert Barnum shakes hands with then-Gov. Bobby Jindal.

John K. Flores: Is it time to go bear hunting?

One evening in the early 90s, I sat listening with great intrigue to my father-in-law tell me how black bears were one of the biggest nuisances to trappers. Pop had trapped all his life and was one of the last marshmen around these parts who made his living down the bayous trapping in the winter and fishing in the spring.

One of the species of animals he trapped was nutria. Nutria are an invasive species and are responsible for loss of wetland habitat due to their voracious appetite for native aquatic plants in the marsh that hold soil together. However, well into the late 80s, nutria fur was quite valuable.

Nutria aren’t one of the brightest animals in the world and to catch them isn’t rocket science. Nutria will walk the same trail in the marsh from thick cover to the edge of the bayou multiple times during the day and night. All a trapper has to do is cut a willow pole, slip the ring of a Victor No. 1 or 2 single or double long spring trap over it, then stab the pole in the marsh to hold the trap.

Once the trap is secure, all you have to do is open the trap’s jaws and set it in the nutria’s trail. You don’t have to hide it or put any scent on it to attract the animal. Nutria will literally walk right on it and get caught. The next morning, when you run (check) your traps, you stand a good chance of catching a nutria.

This was precisely what my father-in-law was alluding to in his bear story. Often a trapper would put out a hundred or more traps along the edge of a bayou. When nutria are abundant their trails aren’t far apart, perhaps no more than 5 yards and often less.

My father-in-law told me how when a bear finds your trapline, you might as well pull your traps, because the bear will kill everything going trap to trap. And, when that occurred, he said, trappers would take matters into their own hands and kill the bear. After all, the bruin was messing with their livelihood.

Due to deforestation in supplying lumber to a growing country, clearing land for agriculture, and legal and illegal hunting in the 19th and 20th centuries, the Louisiana black bear went into steep decline.

The last time there was a statewide bear season in Louisiana was 1987. Considered one of 16 subspecies of black bears in North America, in 1992, the Louisiana black bear was listed as a threatened subspecies on the Endangered Species List.

Following listing, great effort went into restoring black bear populations, where sustainable numbers are now found in St. Mary and Iberia parishes in south Louisiana, Pointe Coupee Parish in the central part of the state, Concordia and Avoyelles in the east-central region, and Tensas, Madison and West Carrol parishes in the northeast.

On March 11, 2016, the Louisiana black bear was officially removed from the endangered and threatened species list.

This month the Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Commission adopted a Notice of Intent to hold a Louisiana black bear hunting season in December of 2024 in Northeast Louisiana. One of the questions is, how many black bears do we currently have in the state to justify a season?

According to Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Large Carnivore Program Manager John Hanks, latest estimates from February 2023 indicate there are roughly 1,212 bears in the state and probably more.

Hanks said, “We do have more than that and it’s probably around 1,500 bears. The stats we have are representative of 80 to 90 percent of the population and don’t take into consideration Caldwell, Morehouse, Richland, and Union parishes where we know we have good populations. We also have bears in Kisatchie National Forest too, so actually it wouldn’t be surprising if there are more than that.”

There are four Louisiana Bear Management Areas, where initially the bear season will be limited to BMA 4 in the northeast part of the state. Ten tags will be issued by lottery and equally distributed between Wildlife Management Area Permits, Private Landowner permits and General Permits. Those with general permits must obtain a landowner’s permission to hunt within the BMA where the season is open.

Hanks says BMA 4 is a region where the Louisiana black bear population is the densest and where they can hold a sustainable hunt and not harm the population. Moreover, season dates have been established to minimize and limit the possibility of harvesting female black bears that should normally be hibernating at that time of year. The Notice of Intent states cubs (75 pounds and less) and females with cubs are not legal to harvest.

Much of the feedback from Louisiana hunters has been positive Hanks says, with the only pushback being from hunters who want to see more tags issued.

Citizens living in St. Mary Parish have had their share of negative interactions with black bears rummaging around under patios, raiding garbage cans, and climbing trees to eat acorns in their yards. And though the local population seems large enough to hold a sustained hunt, currently there is no plan to hold a season in St. Mary Parish.

John K. Flores is the outdoor writer for the Review. He can be reached at gowiththeflo@cox.net.